Near-atomic cryo-EM imaging of a small protein displayed on a designed scaffolding system

Significance

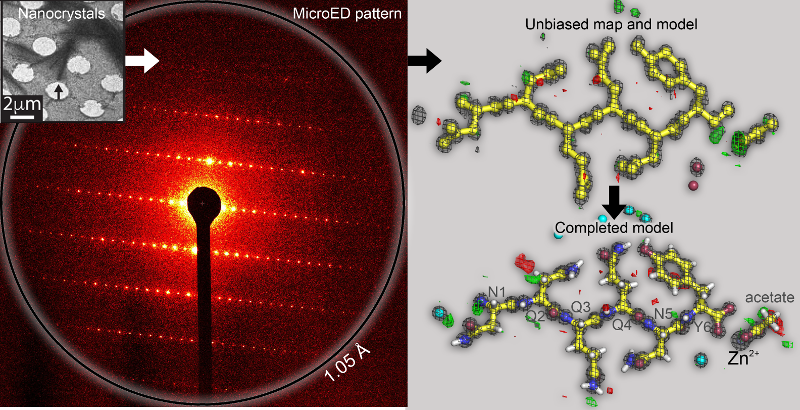

New electron microscopy (EM) methods are making it possible to view the structures of large proteins and nucleic acid complexes at atomic detail, but the methods are difficult to apply to molecules smaller than approximately 50 kDa, which is larger than the size of the average protein in the cell. The present work demonstrates that a protein much smaller than that limit can be successfully visualized when it is attached to a large protein scaffold designed to hold 12 copies of the attached protein in symmetric and rigidly defined orientations. The small protein chosen for attachment and visualization can be modified to bind to other diverse proteins, opening a new avenue for imaging cellular proteins by cryo-EM.

Abstract

Current single-particle cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) techniques can produce images of large protein assemblies and macromolecular complexes at atomic level detail without the need for crystal growth. However, proteins of smaller size, typical of those found throughout the cell, are not presently amenable to detailed structural elucidation by cryo-EM. Here we use protein design to create a modular, symmetrical scaffolding system to make protein molecules of typical size suitable for cryo-EM. Using a rigid continuous alpha helical linker, we connect a small 17-kDa protein (DARPin) to a protein subunit that was designed to self-assemble into a cage with cubic symmetry. We show that the resulting construct is amenable to structural analysis by single-particle cryo-EM, allowing us to identify and solve the structure of the attached small protein at near-atomic detail, ranging from 3.5- to 5-Å resolution. The result demonstrates that proteins considerably smaller than the theoretical limit of 50 kDa for cryo-EM can be visualized clearly when arrayed in a rigid fashion on a symmetric designed protein scaffold. Furthermore, because the amino acid sequence of a DARPin can be chosen to confer tight binding to various other protein or nucleic acid molecules, the system provides a future route for imaging diverse macromolecules, potentially broadening the application of cryo-EM to proteins of typical size in the cell.

http://www.pnas.org/content/115/13/3362.long